Learning how to make chords will help you QUICKLY take your compositions to the next level.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve often struggled to come up with original and soul-grabbing chords in my tracks. Sure, you can use ready-made loops and stick them together, or listen to (and copy) existing tracks you love, but having a basic grasp of how to put your OWN chords together from scratch opens up a whole new world of original possibilities…

A friend asked me recently: “How do you make chords, and how do you know which ones sound good together?”. Well, the key to chords, is, err, “keys”.

Firstly, what’s a chord?

A chord is a combination of three of more notes. Easy. You build chords using notes from within a key.

So, what’s a key?

Well, in music, a key is basically the name given to a collection of notes that can be used together and still sound good. You get major keys and minor keys. Major keys sound happy :), and minor keys sound sad :(. For instance, The key of C Major includes the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B and, when played in a scale, sounds like this:

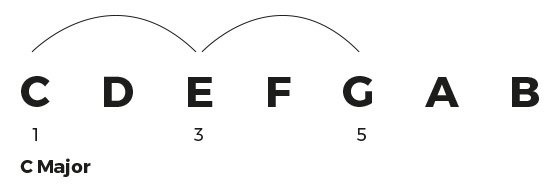

The Key of C Major:

Each note in the key is assigned a number. 1st (or “root”), 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th.

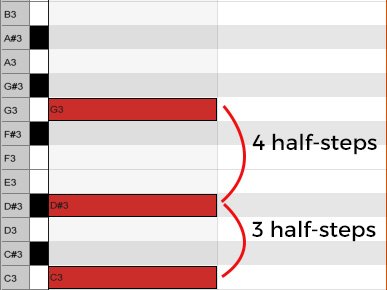

On your DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) piano-roll editor – which is basically a virtual piano – it looks like this:

We can see in the image above that D3 is a two half-steps above C3, E3 is two half-steps above that, F3 is ONE half-step above E3, G3 is two half-steps above F3, A3 is two half-steps above G3, B3 is two half-steps above A3 and C4 (the next octave) is one half-step above B3. The black notes are called “sharps” (“#”) or “flats” (“♭”) depending on what key you’re in, but you don’t need to worry about that too much. Just remember a “#” means play one half-step ABOVE the written note, and “♭” means play one half-step BELOW. *N.B. Your DAW will only display the black notes as”#” and never as”♭” because a) it doesn’t know what key you’re in and b) the “#” symbol is native to software, whereas the “♭” is not.

Chords

Ok, so now we have the basics, we can learn how to make chords. There are loads of different types of chord, but below are the 13 you’re most likely to use, how they sound, and how to make them in ANY key. If you want to really save time, you’re probably most likely to use numbers 1, 2, 5, 8 and 9, so skip to them. We’ll use “C” as the root note in all of them for ease, but you can work out the equivalent chord in any key by counting the intervals between the notes (to see what keys there are and which notes are in them, check out this page).

The 13 Most Useful Chords (5 most common in bold):

1. C Major

2. C Minor

3. C Augmented

4. C Diminished

5. C Suspended Fourth

6. C Major Sixth

7. C Minor Sixth

8. C Major Seventh

9. C Minor Seventh

10. C Dominant Seventh

11. C Major Ninth

12. C Minor Ninth

13. C Dominant Ninth

For each chord, there will be its name, the emotion (I think) it evokes, the notes used, an audio clip of how it sounds, and how it looks in the piano-roll of your DAW:

1. C Major

Sounds: Happy and simple.

Notes: C + E + G

Half-step intervals: Root/4/3

The most common type of chord is called a “triad”. A triad is made up of a root, a third, and a fifth (“root”, “third” and “fifth” refer to the note position within the scale), therefore, a C Major chord will use C, E and G, and look something like this in your piano-roll editor:

Give it a try! Ta-da…your first chord!

To make a major triad in ANY key, simply count 4 half-steps up from the root note for your “third”, and 3 half-steps up from your third for your “fifth”.

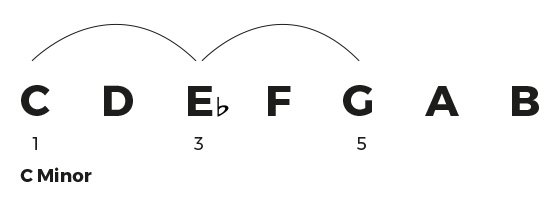

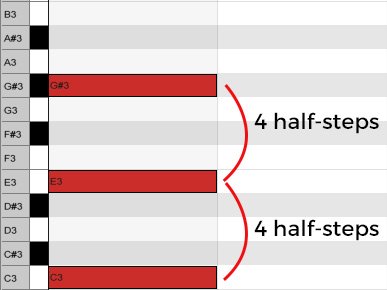

2. C Minor

Sounds: Sad.

Notes: C + E♭ + G

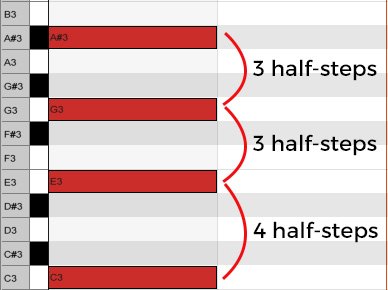

Half-step intervals: Root/3/4

The second most common (and simple) chord, is a minor. Very similar to the major chord, except the third is dropped one half-step, which gives it a “sad” quality.

To make a minor triad in any key, simply count 3 half-steps up from the root for your third, and 4 half-steps up from your third for your fifth.

OK, now we’ve got the most basic two chord-types covered, here are are the other 11 most common types, what they sound like, and how to make them:

3. C Augmented

Sounds: Suspenseful.

Notes: C + E + G#

Half-step intervals: Root/4/4

4. C Diminished

Sounds: Scary.

Notes: C + E♭ + G♭

Half-step intervals: Root/3/3

5. C Suspended Fourth

Sounds: Proud.

Notes: C + F + G

Half-step intervals: Root/5/2

6. C Major Sixth

Sounds: Triumphant.

Notes: C + E + G + A

Half-step intervals: Root/4/3/2

7. C Minor Sixth

Sounds: Sorrowful.

Notes: C + E♭ + G + A

Half-step intervals: Root/3/4/2

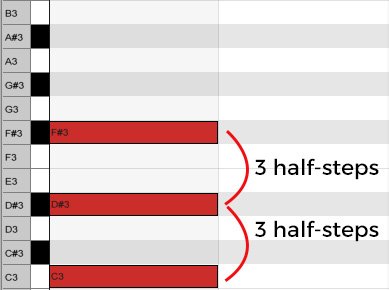

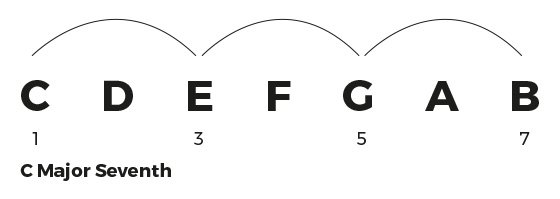

8. C Major Seventh

Sounds: Nostalgic.

Notes: C + E + G + B

Half-step intervals: Root/4/3/4

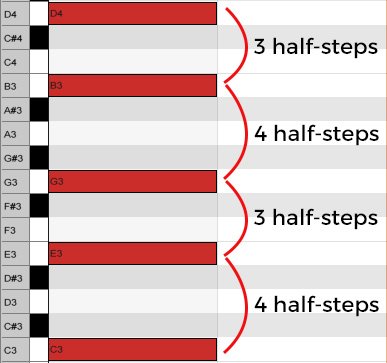

9. C Minor Seventh

Sounds: Melancholic.

Notes: C + E♭ + G + B♭

Half-step intervals: Root/3/4/3

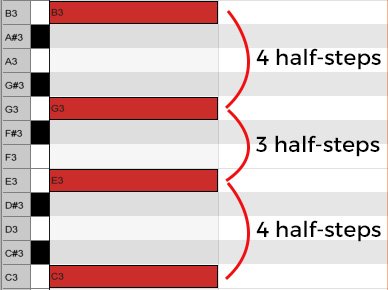

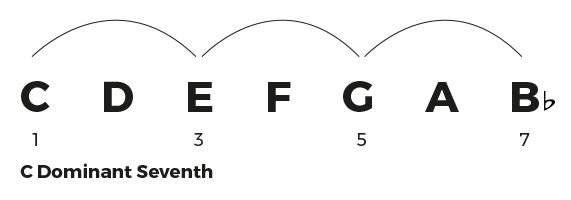

10. C Dominant Seventh

Sounds: Expectant.

Notes: C + E + G + B♭

Half-step intervals: Root/4/3/3

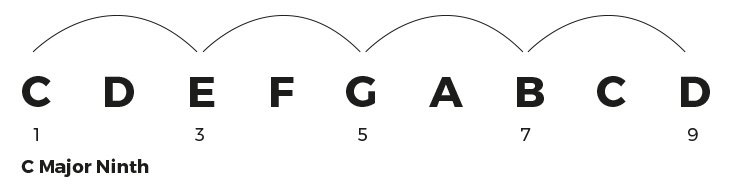

11. C Major Ninth

Sounds: Nostalgic.

Notes: C + E + G + B + D

Half-step intervals: Root/4/3/4/3

12. C Minor Ninth

Sounds: Melancholic.

Notes: C + E♭ + G + B♭ + D

Half-step intervals: Root/3/4/3/4

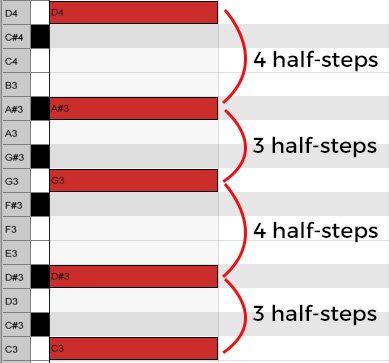

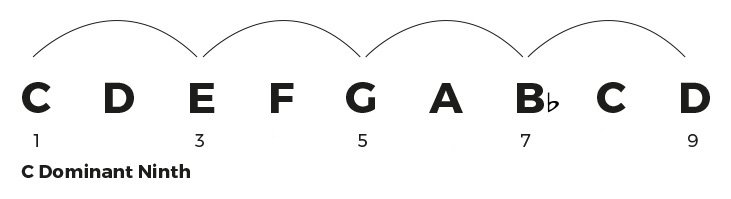

13. C Dominant Ninth

Sounds: Expectant.

Notes: C + E + G + B♭ + D

Half-step intervals: Root/4/3/3/4

Great! So you now know all the chord types you will pretty much ever use! If you want to shake things up a bit, you can use difference “inversions” of each chord. This basically means you swap their order, e.g. a C Major 1st inversion will have E as the root note instead of C, so it would sound and look like this:

Bonus: C Major, 1st Inversion:

Notes: E + G + C

Half-step intervals: 4/3/5

So there you have it! Experiment with different inversions and creating different chords in different keys, and have a go at putting them together. We’ll cover how to sequence them together effectively in another post.

I hope you’ve found this helpful! Do you have any chords you use that I’ve missed, or is anything unclear? Let me know in the comments section below, or post a link to any music you make using these chords. If you like the post, please share it 🙂